- info@aromantique.co.uk

- 07419 777 451

Heather Dawn: Godfrey. P.G.C.E., B.Sc. (Joint Hon)

It is three years since COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) hit the world stage. In spite of the fact SARS-CoV-2 was downgraded by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the UK Government (19th March 2020) as NOT being a ‘high consequence infectious disease‘, draconian measures to apparently control transmission of ‘infection’, overtly and insidiously, were pursued; lockdown, isolation, social distancing, wearing face masks and requirement of perpetual inoculations – terms and conditions that continue to linger in the universal psyche.

Indeed, novel SARS-CoV-2 RNA and DNA modulating ‘vaccines’ (inoculations/injections) were developed at breath-taking speed and by the end of 2020 a universal inoculation programme was rolled out (lockstep) across the globe. The blanket-lockdown across the UK (and globally) was insidiously replaced by self-regulated isolation, the modulated PRC test applied as judge and jailor; the onus of responsibility transferred from government diktat to individual (conditioned and compliant) with a swift sleight of hand.

Summer, with its long lingering days, sunshine and warm weather, invites a logical, welcomed lull in behavioural distancing and protection. ‘Flu season, however, returns each winter, heralding renewed focus on transmission and revitalised recommendation to ‘get jabbed’. Face masks are still required in some public spaces (transport, entertainment venues, GP surgeries, hospitals, schools and so on). But what protection from infection (its spread or contraction) do face masks really provide?

The following article looks at the physical function and consequence of wearing a face mask and whether or not face masks prevent or inhibit viral infection, in particular, SARS-CoV-2. Commencing with a contextual background overview of the function of breathing, the practical value of wearing a face mask is then explored.

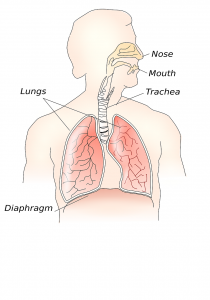

The lungs – breathing in, breathing out

The atmospheric, ambient air we breathe typically consists of around 78% nitrogen and 21% oxygen, with the remaining 1% consisting of a combination of carbon dioxide, helium, methane, argon and hydrogen.

Breathing is the regular inflation (breathing air in) and deflation (breathing air out) of the lungs; the lungs maintains a steady concentration of atmospheric gases in the alveoli and facilitate constant mobilisation of oxygen (intake) and carbon dioxide (excretion).

For example, oxygen rich air drawn into the lungs is absorbed by the alveoli and momentarily held in suspension just long enough to facilitate gaseous exchange; carbon dioxide infused air is then exhaled from the lungs.

For example, oxygen rich air drawn into the lungs is absorbed by the alveoli and momentarily held in suspension just long enough to facilitate gaseous exchange; carbon dioxide infused air is then exhaled from the lungs.

What is gaseous exchange?

The walls of the alveoli and its capillaries are only one cell thick; both alveoli and capillaries are semipermeable, thus, the process of diffusion is enabled. Diffusion is described as the movement of a substance (in this case, oxygen and carbon dioxide) from an area of high concentration to an area of low concentration.

So, for example, oxygen, which is present in higher concentration in air breathed in and absorbed by the alveoli, diffuses down the concentration gradient through the walls of the capillaries within the alveoli to the blood. The blood then, in turn, carries oxygen in solution in blood water, and also in chemical combination with haemoglobin (a blood protein) as oxyhaemoglobin (found in red blood cells – see below), to tissues throughout the body – tissues which form the brain and other organs, muscle, skin and so on.

Conversely, and at the same time, carbon dioxide, which is in higher concentration in the blood channeled from the organs to the lungs, passes in the opposite direction; that is, diffusing out through blood capillaries into the alveoli from where the carbon dioxide then diffuses into the lungs, and thence is exhaled within the outward breath into the external atmosphere. Some water is also excreted from the body within breath during exhalation (observed on cold days in the cloud-like vapour issuing from nose and mouth).

This process of gaseous exchange is known as respiration.

Respiration and the vital role of oxygenating cells

Gaseous exchange not only occurs in the lungs but also within cells throughout the body; that is, oxygen is absorbed and carbon dioxide is excreted through diffusion (respiration). Diffusion occurs when oxygen, which is in higher concentration in the blood than in cells and interstitial fluid surrounding cells, diffuses down the concentration gradient moving from capillaries to cells. At the same time carbon dioxide, which is a waste product of cell metabolism and present in higher concentration in the cells and interstitial fluid, diffuses down the concentration gradient from the cells to the blood (in exchange).

Gaseous exchange not only occurs in the lungs but also within cells throughout the body; that is, oxygen is absorbed and carbon dioxide is excreted through diffusion (respiration). Diffusion occurs when oxygen, which is in higher concentration in the blood than in cells and interstitial fluid surrounding cells, diffuses down the concentration gradient moving from capillaries to cells. At the same time carbon dioxide, which is a waste product of cell metabolism and present in higher concentration in the cells and interstitial fluid, diffuses down the concentration gradient from the cells to the blood (in exchange).

Carbon dioxide is then transported within blood to the lungs by three different mechanisms:

Oxyhaemoglobin is an unstable compound and breaks up (dissociates) easily to liberate vital oxygen.

Factors that increase dissociation of oxyhaemoglobin include raised carbon dioxide content within tissue fluid, raised temperature, and a substance known as 2,3-BPG present in red blood cells. For example, in active tissues there is an increased production of carbon dioxide and heat, that in turn leads to an increased availability of oxygen (facilitated through the process of diffusion as previously described); oxygen is then readily available to those tissues in greatest need. (Wilson & Waugh 1998)

Exercise and physical activity supports gaseous exchange, increases cell oxygenation and promotes removal of waste material (including carbon dioxide) from cells. Consuming sufficient water (H2O), which contains oxygen, also supports oxygenation and cell cleansing, and replaces water lost via the lungs through gaseous exchange, sweating, urinating and defecation.

Respiration in turn creates the energy-producing chemistry (for example, glucose) that drives the metabolism of the body and most living things. Oxygen, therefore, is vital to life. Equally, the body’s unencumbered ability to absorb nutrients and eliminate waste, including carbon dioxide, from cells, from the lungs, and from the process of digestion (through the gut), is also vital to health, and ultimately, vital to life.

According to the Cabinet Office and the Department of Health and Social Care, ‘in the context of the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, a face covering is something which safely covers nose and mouth; these may be cloth coverings or disposable coverings’. Apparently, the purpose of this advice is not so much to protect the wearer but, rather, to protect other people, especially the elderly and physically vulnerable, against contraction and spread of viral disease; this decree assumes the wearer is infected whether they display symptoms or not (asymptomatic).

But is wearing a mask in this context actually beneficial – for individuals and society? Does wearing a mask prevent the spread of infection?

Masks have been worn throughout history: for example, to protect the face during battle; as decorative adornment during celebrations and rituals; to obscure identity; to prevent inhalation of noxious fumes, pollution and large dust particles. During the middle ages, for example, plague doctors wore beak-shaped masks – the beak was stuffed with scented herbs and/or flowers to filter and dispel bad smells (miasma); bad odours were thought to be the vector of disease.

Masks have been worn throughout history: for example, to protect the face during battle; as decorative adornment during celebrations and rituals; to obscure identity; to prevent inhalation of noxious fumes, pollution and large dust particles. During the middle ages, for example, plague doctors wore beak-shaped masks – the beak was stuffed with scented herbs and/or flowers to filter and dispel bad smells (miasma); bad odours were thought to be the vector of disease.

Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) proposed the notion of bacteria (viruses, which are nano particles even smaller than bacteria, were yet to be discovered) as an airborne contagion in 1861. His theory assumed that germs are the vectors of disease. Pasteur’s notion was contested at the time by Antoine Bechamp (1816-1908), who contended that symptoms of disease are expressions of ‘outfections’ (Young 2021), rather than ‘infection’ – that is, instead of bringing disease to the body, bacteria are purposefully present at the site of disease to ‘clean up’ the terrain; sweating, fever, headaches, muscles aches and pains, diarrhoea etc. are symptoms of outfection, that is, of the body ridding itself of toxic waste products.

Bechamp’s terrain theory, however, was ridiculed and rebuked, he was labeled a ‘crank’ (Pontin 2018, Young 2016) and his proposition was summarily dismissed (although, discussion and deliberation about Bechamp’s terrain proposition has currently re-emerged). Pasteur’s germ theory prevailed, and apparently readily gained private and public support. Pasteur’s notion that germs (assumed as invasive microscopic vectors of disease) are everywhere, consequently, prompted greater emphasis and attention toward cleanliness and hygiene (hand washing, sterilisation of environments, wearing protective garments during medical procedures and so on). Doctors prescribed wearing face masks during outbreaks of infection, epidemics and pandemics, in attempt to limit the spread of infection (or germs). Lace veils were worn by women during this era as a fashion accessory to protect their lungs from harmful airborne particles (found in coal induced smog, smoke and dust dispersed into the atmosphere).

Science, however, has progressed considerably since the nineteen hundreds. Today, electron microscopes enable insight into realms previously never imagined (hence the apparent discovery of viruses and exosomes, and other such nano particles). So, what does modern science reveal about the efficacy of wearing face masks to prevent the infectious spread of viruses and germs?

Discussing respiration, Baruch Vainshelboim (2021) reminds us in his article Face masks in the COVID-19 era: A health hypothesis):

It is well established that acute significant deficit in [oxygen] O2 (hypoxemia) and increased levels of [carbon dioxide] CO2 (hypercapnia), even for few minutes, can be severely harmful and lethal; while chronic hypoxemia and hypercapnia cause health deterioration, exacerbation of existing conditions, morbidity and ultimately mortality.

Emergency medicine demonstrates that 5–6 minutes of severe hypoxemia during cardiac arrest will cause brain death with extremely poor survival rates. On the other hand, chronic mild or moderate hypoxemia and hypercapnia, such as from wearing facemasks, results in shifts to higher contribution of anaerobic energy metabolism, decrease in pH levels and increase in cells and blood acidity, toxicity, oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, immunosuppression and health deterioration.

In conclusion Vainshelboim states:

The data suggest that both medical and non-medical face masks are ineffective to block human-to-human transmission of viral and infectious disease such SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 – [this] supports against the usage of face masks. Wearing face masks has been demonstrated to have substantial adverse physiological and psychological effects. These [effects] include hypoxia, hypercapnia, shortness of breath, increased acidity and toxicity, activation of fear and stress responses, rise in stress hormones, immunosuppression, fatigue, headaches, decline in cognitive performance, predisposition for viral and infectious illnesses, chronic stress, anxiety and depression. Long-term, wearing a facemask can cause health deterioration, developing and progression of chronic diseases, and premature death. (read the full article here)

Our first intake of breath at birth is absolutely vital for ‘life’, followed closely by our need for fluid, then nutrients – ‘is he/she breathing?’ is the immediate concern for the new born infant entering the world; every single breath issued from that first moment sustains life, breath by breath, throughout life, and is vital for appropriate organ and brain function. The gaseous content and balance of the air we breathe is available to us at the perfect ‘pitch’ or balance to sustain our existence. Health of the organism is determined by the properties and qualities, primarily of the atmosphere, fluids and nutrients we consume (nutrients also includes thoughts, emotions, intentions etc.).

Face masks cover nose and mouth and consequently interfere with the gaseous content and balance of air inhaled and exhaled and impede efficient respiration. For example, wearing a face mask reduces intake of vital oxygen by 15% and excretion of CO2 by the same amount, and thus creates an acidic internal environment (which in turn increases susceptibility to illness and disease). (Young 2021) Face masks also increase the temperature and moisture retention between the face mask and skin, and also within nose and mouth cavities, and the lungs. Face masks impede efficient exhalation of toxins and waste products (including and other than CO2) excreted from fluids and tissues within the body. Yet, face masks do not impede inhalation or exhalation of infinitesimally small viral nano-particles, viruses, exosomes, fungi or other unidentifiable fragments. Further, bacteria and germ components (which are larger than virus and exosome particles) cling to the inner and outer surface of the (warm, moist) mask, thus, the perfect environment for bacteria and fungi to grow and proliferate is created, increasing opportunity and propensity for infections of skin beneath the mask, mouth, throat, nasal cavities and lungs to develop. (Vainshelboim 2021)

Not all face masks are the same, however. MacIntyre et al (2015) conducted a randomised trial to evaluate the efficacy of wearing cloth masks compared to wearing medical mask in hospital by healthcare workers. They found that ‘penetration of cloth masks by [micro] particles was almost 97% and penetration of medical masks, 44%’. Rates of infection (clinical respiratory infection, influenza-like illness and laboratory-confirmed respiratory virus) were higher in the cloth mask arm of the study. Neither cloth nor medical masks, however, prevented penetration. The authors warned that moisture retention, re-use of cloth masks and poor filtration may result in increased risk of infection, and they cautioned against the use of cloth face masks.

Bae et al (2020) conducted a study to ascertain the ‘effectiveness of surgical and cotton masks in blocking SARS-CoV-2’ (COVID-19), concluding that neither surgical nor cotton masks effectively filtered SARS-CoV-2 during coughs by infected patients; microscopic CV particles passed through both types of mask. They also acknowledged “we do not know whether masks shorten the travel distance of droplets during coughing, [suggesting] further study is needed to recommend whether face masks decrease transmission of virus from asymptomatic individuals or those with suspected COVID-19 who are not coughing.”

In another study, Sharma et al (2020) carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the efficacy of wearing cloth face masks to prevent coronavirus infection transmission. They conclude that ‘cloth masks have limited efficacy in combating viral infection transmission’; ‘efficacy of cloth face masks filtration varies and depends on the type of material used, number of layers, and degree of moisture in mask and fitting of mask on face’. Even so, in spite of acknowledging that cloth face masks offer inadequate prevention, they suggest that ‘cloth masks may be used in closed, crowded indoor, and outdoor public spaces involving physical proximity to prevent spread of SARS-CoV-2 infection’.

Conclusion

Face masks do not provide meaningful protection against viral infection. At best, they may temporarily, partially reduce viral nano-particle transmission via the respiratory system, but not by any meaningful amount. Equally of concern, wearing a face mask inhibits appropriate respiration, thus compromising the immune system, and creates an environment under and around the mask that encourages proliferation of bacteria and fungi. Face masks, therefore, do not prevent transmission of viral (or other nano or micro) particles, and are likely to create unfavourable conditions for the person wearing the mask, potentially leading to insufficient and impeded respiration, infection of the respiratory system and thus poor systemic function, especially when they are worn for long periods of time.

Face masks, however, are often used in industry, or when undertaking DIY activities, and may reduce inhalation of large particles, such as from dust (saw dust, dirt, fibres etc.), and moisture created by sprays (water, chemicals, paints etc.). Even so, the same health concerns apply as above, so frequent replacement with a new or clean face mask, along with ‘fresh air’ breaks, and limited duration of use, is a vital and sensible precaution.

In the context of infection, whether viral, bacterial or fungal, it appears sensible to proactively bolster and support the immune system (increased vitamin and mineral intake, maintaining a healthy, fresh and varied diet to ensure appropriate nutrition, exercise, fresh air, sunshine and vitamin D absorption/synthesis, and so on). Inhibiting effective and efficient respiration (the negative result of which is toxification of the internal terrain and unnecessary burdening, thus weakening, of the immune system) through wearing a face mask is counterintuitive. If a person is unwell and/or expresses obvious symptoms of COVID-19, or any other corona virus or respiratory infection, they may, of their own volition self isolate and apply appropriate wellness care and, if necessary, seek medical care, until symptoms desist.

The choice to wear a face mask or not depends on the context, risks and benefits of a given situation. Longterm wearing of a face mask, no matter the instigating reason or purpose, is potentially harmful to health. Asymptomatic people do not spread disease, and symptomatic people may actually exacerbate their condition through wearing a face mask. Face masks prevent contamination, inhalation or expression of large drops or particles of fluid or debris but do not prevent the spread of disease per sa. A strong immune system and sensible (but not obsessive) hygiene measures support resilience; if infected, a healthy immune system will help support and aid recovery; appropriate nutrition and a healthy balanced lifestyle bolsters and supports natural immunity. To mask or not to mask? Choose wisely; a considered personal choice, not enforced diktat. Fresh clean oxygen-infused air is quintessential for good health, and life.

References

People wearing masks image: Image by <a href=”https://pixabay.com/users/andremsantana-61090/?utm_source=link-attribution&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=image&utm_content=5306374″>André Santana AndreMS</a> from <a href=”https://pixabay.com/?utm_source=link-attribution&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=image&utm_content=5306374″>Pixabay</a>

Bea et al (2020) Effectiveness of Surgical and Cotton Masks in Blocking SARS-CoV-2: A controlled comparison in 4 patients. American college of physicians. Public Health emergency collection. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7153751/

Face coverings: when to wear one, exemptions, and how to make your own.

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/face-coverings-when-to-wear-one-and-how-to-make-your-own/face-coverings-when-to-wear-one-and-how-to-make-your-own

MacIntyre, C. R. et al (2015) A cluster randomized trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers. British Medical Journal. Infectious Diseases. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/5/4/e006577

Pontin, J. (2018) The 19th-Century crank who tried to tell us about the microbiome: Wired. https://www.wired.com/story/the-19th-century-crank-who-tried-to-tell-us-about-the-microbiome/

Sharma, K. S., Mishra, M., Mudoal, S. K. (2020) Efficacy of cloth facemask in prevention of novel coronavirus infection transmission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7497125/

Vainshelboim, B. (2021) Facemasks in the COVID-19 era: A health hypothesis. PebMed.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7680614/

Wilson, K. J. W.; Waugh, Anne (1998) Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness. Churchill Livingstone, London

Young, R. O. (2016) Who had their finger on the magic of life- Antoine Bechamp or Louis Pasteur? MedCrave online https://medcraveonline.com/IJVV/who-had-their-finger-on-the-magic-of-life—antoine-bechamp-or-louis-pasteur.html

Bibliography

Coleman, V. Dr. (2020) Proof that masks do more harm than good: Brand New Tube https://brandnewtube.com/watch/proof-that-face-masks-do-more-harm-than-good_5Ya8cJN5eCT3vqj.html